I just finished reading The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt & the Fire that Saved America, by Timothy Egan.

I just finished reading The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt & the Fire that Saved America, by Timothy Egan.

It’s the first historical book I couldn’t put down.

It’s the riveting story of how Teddy Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot invented the radical notion of conservation and masterminded a new agency: the National Forest Service. It’s also the dramatic story of the first Forest Service employees and the massive fire they fought in August 1910. The Big Burn – 3 millions acres of scorched earth – secured the future of the Forest Service and the legacy of Roosevelt, Pinchot and the brave fire fighters who took on an impossible task.

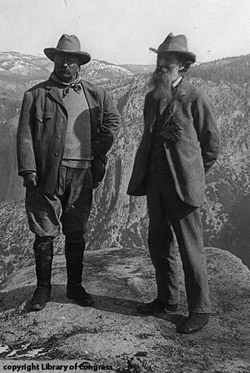

If ever there was an outdoor President, it was Teddy Roosevelt. He thrived in the outdoors and it was his persona that inspired the movement to save vast tracks of land from clear-cutting. In addition to Pinchot, Roosevelt was friends John Muir. Muir’s prophetic voice was very influential to this story and fueled Roosevelt’s bold conservation initiatives which included designating the first National Monuments and congressional designation of Yosemite National Park.

After reading this book, I’m clear that America’s psyche was founded on wide open spaces. As a people, we constantly pushed toward open land until there was no more open land and resources left. All forested land would have been logged if Roosevelt hadn’t stepped in and made conservation a household word. Roosevelt, Muir and Pinchot loved the west and talk eloquently about the healing powers of nature, hiking, and the need to preserve places for desperate city dwellers. This remains even more true today. Cities are larger. Technology keeps us tied to computers and machines. Lives are moving faster than ever before and open spaces continue to shrink. In 1908, most people still lived on farms. Today, just a handful remain closely connected to the land. Kids have become increasingly removed from the very source of rejuvenation.

Richard Louv would likely take this one step further and say that without nature we are removed from a powerful source of creativity.

While Louv cites no study that proves this, it could be said that wilderness, or more broadly, outdoor adventure and exploration, fueled the invention and creativity that built this country. This does makes sense. Out of all the things that we have in America that no one else in the world has, it’s our wide open spaces and unsurpassed natural beauty and resources. We have Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, Glacier National Park, the Boundary Waters and many, many, more places. To be sure, there are beautiful places everywhere, but ours are so accessable. Furthermore, our outdoor legacy is our history. Good or bad, our history is full of adventure and outdoor exploration. Today, we have a parks system that makes visiting these places relatively easy and interpretive programs that make our visits meaningful. It makes sense that Roosevelt and Pinchot hatched the idea of conservation just as the frontier had closed. Could it be that in addition to saving something for future generations, Roosevelt didn’t want to lose what made us American? If we chopped down all the trees, perhaps we wouldn’t recognize ourselves or who know who we are. Would we still know how to think big thoughts or dream big dreams?

Louv writes in his book about how a young Benjamin Franklin and his friends created a water diversion system in their spare time, claiming that the land fueled his genius for invention.

It certainly can’t hurt. Where else, but in the outdoors, do all the senses become piqued. Who isn’t moved by the Grand Canyon and come away a slightly different person? I know I was. My visit makes me all the more hungry to return because I never know what magic will happen. There is a timelessness in huge places. A feeling of being small and of knowing your place against such a massive backdrop. I take heart in that knowledge because it keeps me humble knowing that I can’t change most of anything in the world. I am but a visitor.

I hope to give kids that feeling by getting them outside. We may not get to the Grand Canyon, but I can assure you that the landscape is no less healing and no less a place to hatch big ideas then it was in Roosevelt’s time. It’s certainly a place to start.